By Eliot Lees and Chris Watson

No, the Boeing 737 isn’t going to disappear anytime soon. But that doesn’t mean electric aviation won’t be here sooner than you think.

In fact, smaller electric aircraft are already a reality thanks to current battery technology, systems, and propulsion—and these aircraft will begin the transformation to an all-electric fleet in the nine-seat, short-haul “air taxi” or “commuter” market segment.

Short-haul travel, defined as 200 to 500 nautical miles, is a relatively small segment of air travel in the United States today. However, this segment will be the leading-edge of how we travel in the future. Short-haul travel offers fast, efficient, and uncongested flying as an attractive alternative to the automotive traffic jams of the present.

Economics of short-haul aviation

Today, the economics of short-haul aviation don’t work. Piston and turboprop aircraft are expensive to operate and maintain, making driving the much-preferred option for travelers. Travelers currently pay approximately $1.00 to $2.00 per passenger mile to fly on commuter aircraft, making the cost between three and eight times more expensive than driving.

Source: ICF Analysis

While conventional aviation can achieve lower costs with economies of scale, the costs are only noticeably lower for aircraft with 70 seats or more. However, there are only a limited number of routes that have sufficient volumes to fill regional jet or narrowbody jet aircraft seats; as a result, short-haul aviation in the United States has been in decline over a number of decades, as consumers chose the flexibility of driving over flying.

Today’s electric motors and battery technology will reduce direct operating costs by approximately 80% compared to current piston or turboprop aircraft. Altogether, we estimate that over the next five years, electric aircraft technology will drive down the cost of short-haul flying to a level slightly below today’s narrowbody aircraft. We estimate the end cost to travelers will be competitive with driving, considering reduced travel time.

Airlines will still need to figure out viable business models to fill seats and generate sufficient load factors to make money, but the economics of electric aviation will allow this travel segment to become a game-changer.

Easy, convenient, affordable

The vision of short-haul travel is ease and convenience at an affordable price. Today, the option is to fly from a major commercial service airport. This option often takes a passenger several hours to pass through security and arrive at the gate in time to board, lengthening a one-hour flight into a far longer journey. When considering the inflexibility of flights, it’s understandable why most people choose to drive.

Source: ICF Analysis

But compare the alternative using a nine-seat electric aircraft. Instead of flying from a major airport, travelers will be able to use a more convenient general aviation airport. Because the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) classifies nine-seat aircraft as “air taxi,” it does not require security screening. Thus, the traveler can breeze from parking lot to aircraft with only a minimum of hassle. And the traveler will likely do all of this with an app. Using today’s rideshare services, a car can pick up the traveler at their house and meet them at the arriving airport to chauffeur them to the final destination.

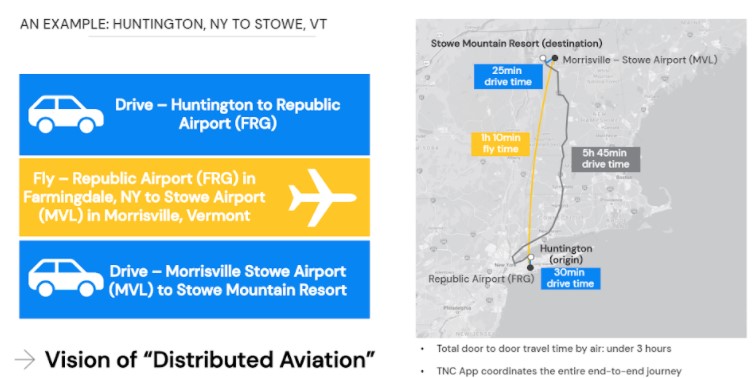

Consider the example of two people traveling from Long Island, NY to Stowe, VT for a ski trip:

-

Driving door-to-door from Long Island to Stowe would take five hours and 45 minutes.

-

Driving to Newark Airport (EWR), flying to Burlington, Vermont (BTV), then driving to Stowe would be comparable with all of the parking, security screening, and wait time.

-

Taking a rideshare to a nearby general aviation airport, flying to a general aviation airport near Stowe, and being driven to the final destination would be half the time.

This third option is the vision of a more “distributed aviation”.

Source: ICF Analysis

New craft, new infrastructure

The FAA is currently evaluating several prototypes of electric aircraft.

One type is a fixed-wing electric aircraft, which will fly the same mission of today’s piston or turboprop aircraft but with far superior operating economics.

The second type is an electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing (“eVTOL”) aircraft. This aircraft has operating characteristics similar to a helicopter, with the potential to fly non-traditional point-to-point routes—avoiding airports altogether.

The FAA expects to certify the first wave of electric aircraft by the end of 2023. Once that occurs, airlines will start introducing them into the U.S. commercial fleet, beginning a demonstration period that will take several years to develop the proof of concept. This proving-out period would highly restrict eVTOL operations at first; this type of aircraft will fly mostly from airports and on a scheduled basis until the concept becomes more widely accepted.

During the decade between 2025 and 2035, this class of aircraft will enter the fleet in significant numbers. We estimate the U.S. fleet requirement for electric aircraft to reach 3,300 by 2035. Based on these estimates, we project the passenger segment of the electric aviation market will reach $52 billion within 15 years. (Note: These forecasts represent only the airport-to-airport segment of the market, and do not include the potentially larger off-airport advanced air mobility, or AAM, market).

In it for the long haul

Whatever the future of aviation looks like in the coming years, especially as the industry recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, electric aviation will undoubtedly be playing more and more of a prominent role.

While electric aviation is starting with short-haul flights, with the right technology and infrastructure, it could remain with us for the long haul.

Facebook comments